Robusta is a brand name for the species that was chosen to showcase its characteristics. It was discovered in the late 1800s in the Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and its commercial potential was obvious. It could grow and fruit at lower altitudes, in higher temperatures, and was disease resistant than conventional Arabica plants.

These characteristics continue to drive much of Robusta production today, and because of how it is produced, it is significantly less expensive.

However, there is an unavoidable drawback: it doesn’t taste particularly nice.

Some will argue that a well-produced Robusta coffee tastes better than a poorly produced Arabica coffee, which may be true, but it does not persuade us that Robusta tastes excellent. It’s tough to assign specific flavors to coffees, but I believe it’s fair to state that Robusta has a woody, burnt-rubber flavor in the cup. It normally has a low acidity level but a thick body and texture.

There are many quality levels within Robusta, and it is possible to develop higher-quality Robustas. For many years, it has been a staple of Italian espresso culture, but nowadays, the majority of Robusta produced throughout the world ends up in massive production plants destined to become our industry’s pariah: instant soluble coffee.

Price is significantly more essential than flavor in the soluble coffee market. Due to the global reliance on coffee as a fast-food commodity, Robusta accounts for over 40% of all coffee produced yearly.

This percentage is subject to change due to price and demand fluctuations. For example, if coffee prices rise worldwide, international coffee businesses may be forced to discover cheaper alternatives to Arabica, resulting in greater Robusta production.

Interestingly, there has been a declining tendency in coffee consumption when roasters switched Robusta coffees for Arabica in large commercial blends.

This could be due to the fact that Robusta has roughly twice as much caffeine as Arabica. Consumers notice – or, at the very least, modify their coffee-drinking habits – when huge brands cut shortcuts in any way.

The Genetics of Coffee

Until a fairly remarkable genetic discovery, the coffee industry considered Robusta an unattractive sibling to Arabica. After sequencing the genomes, scientists discovered that the two species are not cousins or siblings. On the other hand, Robusta looks to be Arabica’s parent.

Robusta crossed with another species called Coffea euginoides and developed Arabica, most likely in southern Sudan.

Ethiopia, long thought to be the home of coffee, saw this new species spread and prosper.

There are currently 129 species of Coffea, most of which are substantially different from the plants and beans we are familiar with, thanks to the work of Kew Gardens in London. Many of these species are native to Madagascar, although others can be found in parts of southern Asia and even Australia.

At the moment, none of these species are receiving commercial attention, but scientists are becoming more interested in them as a result of a problem in the coffee industry: the lack of genetic variation among the plants now under cultivation.

Because of the global spread of coffee, we now have a global crop with a common ancestor. The genetic make-up of coffee plants is rather uniform, putting world coffee production at risk. Phylloxera, an aphid that decimated wide swaths of grapevines across Europe in the 1860s and 1870s, taught the wine business that a disease that can affect one plant may likely affect all of them.

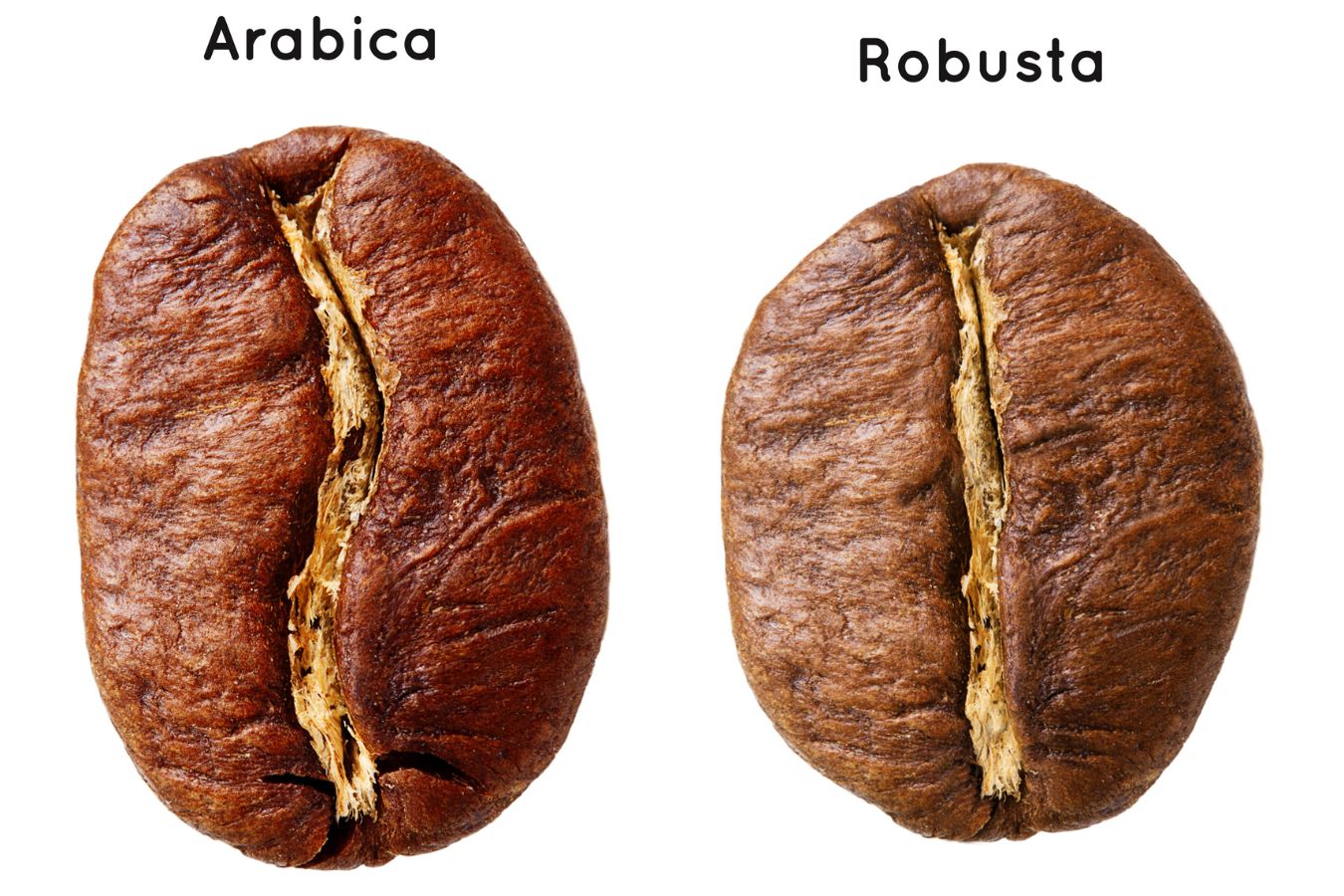

Growth of Arabica vs Robusta beans

The Robusta bean comes in a variety of subtypes, each with its own set of traits. Arabica beans are the same way. Compared to Arabica, Robusta varietals have a higher disease resistance and production capacity. Robusta flourishes in regions where Arabica would be destroyed by fungus, other diseases, and pests because it grows well at lower altitudes.

Robusta is a larger plant than Arabica, nearly twice its size, and thrives under higher humidity. The berries take approximately a year to ripen after blossoming. Because Robusta is self-sterile, it requires cross-pollination from the wind, bees, and other insects to reproduce.

Robusta coffee

Robusta coffee beans, Arabica’s street-smart younger brother, is the most prevalent Coffea Canephora varietal. Robusta is often utilized in espresso blends despite its less refined flavor.

It is recognized to generate a greater crema (the creamy layer found on top of an espresso shot) than Arabica. It’s tougher, disease-resistant, and provides higher yields. It also has a higher caffeine content!

Arabica coffee

Despite having less caffeine than Robusta, Arabica beans are frequently thought to have a better flavor. Arabica has a smoother, sweeter flavor profile, with chocolate and sugar undertones. They often have grape or berry undertones. Conversely, Robusta has a gritty or rubbery flavor with a stronger, harsher, and more bitter taste.

According to the International Coffee Organization, Arabica farmers produce more than 60% of the world’s coffee. This was the sort of bean that began Ethiopia’s coffee history, and it still thrives at higher elevations. Arabica flowers are fragrant and develop after a few years, producing ellipsoidal fruits with two flat seeds known as coffee beans inside.