Coffee beans traded in the 1800s

The bulk of coffee was still sold loose in the green in the 1870s for home roasting and grinding America; by the 1930s, more than 90% of coffee sold by merchants had been pre-roasted and provided in ready-weighed, trade-marked containers. It was usually pre-ground as well, though some supermarket chain shops, where the bulk of coffee is currently purchased, made a show of grinding it at the time.

Large-scale roasters were able to establish themselves by manufacturing branded goods that took use of the newest developments in packaging technology thanks to the advent of mass distribution methods such as chain shops, mail orders, print, and radio advertising. In 1900, Hills Brothers, for example, released vacuum-packed jars of canned coffee roast and ground beans.

Consumers were given little information about the contents of these blended ones of the 34 popular branded products illustrated in the 1935 edition of Ukers’ classic text All About Coffee indicated a geographical origin, even the supposedly premium Yuban (Ukers, 1935, pp. 383, 388, 403, 441, 451, 408).

Consequently, as a J. Walter Thompson survey found in the 1920s, although 87% of housewives cited flavor as the most important factor in their brand choice, “it was extremely difficult for the average person to make clear distinctions where the flavor is concerned.”

One copywriter highlighted how “the housewife experiments with percolators, with drip coffee, with Silex machines, and still most of the time the coffee isn’t right. She is battered and bewildered by new packages and new brands, by advertising” (Prendergast, 2010, pp. 157, 189).

Advertisers focus on women

Advertisers preyed on people’s anxieties of not knowing enough about coffee. Housewives faced the We ConsumersdTastes, Rituals, and Waves danger of being beaten, having coffee thrown in their faces, or even being spanked by their husbands for serving them badly prepared coffee on their return from work, according to the big roasters. The remedy, of course, was to use their branded items exclusively (Morris and Thurston, 2013, pp. 220e222) (Fig. 19.2).

Women were targeted in other ways too. Eleanor Roosevelt broadcast to the women of the nation in her radio talks entitled “Over our Coffee Cups,” a show sponsored by the Pan-American Coffee Bureau set up to promote coffee consumption. Slots around the talks sought to persuade listeners of additional reasons and occasions to drink coffee. For example, the cover girl and actress Jinx Falkenburg told radio listeners in 1941.

The best way I know for a girl to look her best at all times is to eat the right things, get plenty of sleep, yes, and drink plenty of coffee. Why do I mention coffee? Because I’ve found that when I want to look fresh and, well, you might say, “blooming in the evening,” coffee is really a wonderful help. After all, you look as well as you feel, and coffee makes me feel cheerful and peppy.” ANNOUNCER: Why not try a delicious, flavorful cup of coffee with your evening meal tonight? And see how much more you get out of life with coffee. Roosevelt (1941)

Outside the house, coffee consumption production was increasing as a result of new food patterns, particularly a preference for light midday meals throughout the working day. Coffee was provided as a beverage to complement, rather than follow, a food such as a sandwich, at venues like lunch counters, soda fountains, and diners.

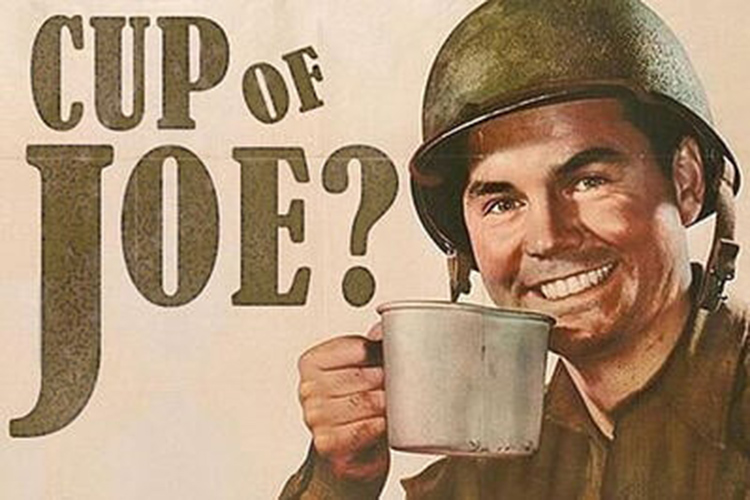

After it was established that free coffee improved productivity among defense employees during World War II, some manufacturers began distributing it as a work incentive. By the end of 1952, 80 percent of American businesses had implemented a coffee break, thanks to a Pan-American Coffee Bureau campaign (Prendergast, 2010, p. 221).

Changes when The Making of the American “Cup of Joe”

These new consumption practices shaped the creation of a distinctive American coffee style. The volume in the cup (or cups) was comparatively large, to last sufficiently long to accompany eating. The body was thin and the flavor was weak, reflecting the dominance of bland Brazilian beans in the blends, as well as the parsimonious nature of housewives who used very lowbrow ratios when preparing coffee, principally by using percolators that over-extracted the beans by repeatedly passing boiling water through them.

In fact, in the post-World War II era, those features were emphasized. The main roasters responded to a drop in per capita consumption by decreasing costs and seeking coffee to steal market share from one another by saying that their brands could be used more cheaply, with Folgers boasting that consumers could use “one fourth less” of their “rich” mix.

Some restaurant roasters shifted to selling coffee in 14 oz. packs, saying that they could now be used to brew the same quantity of coffee as the original 1 pound bags (Prendergast, 2010, p. 223). This was what was used in the “unlimited refills” offered by diners and fast food outlets, served out of the pour-over jugs bulk brewed and left on the hotplate, that came to define the taste of the American “cup of Joe” da term first coined in the 1930s (Mikkelson, 2009).

The corporate giants wasted an opportunity to educate the public into paying a premium for quality coffee goods by continuing to focus on pricing while disguising the nature of their blends (thereby allowing them to further cheapen them by adding Robusta).

Despite the fact that one campaign, the Colombian coffee growers’ federation’s creation of the character Juan Valdez, a peasant farmer growing coffee in the shade at 5000 feet in the Andes, led to a 300 percent increase in Americans identifying Colombian coffee as the world’s finest within 5 months of its introduction in 1960, pressuring many companies into introducing “all Colombian” brands, led to a 300 percent increase in Americans identifying Colombian coffee as the world’s (Prendergast, 2010, pp. 259e260).

Similarly, the corporate giants’ continued focus on housewives and their fears of preparing coffee beans for their husbands not only succeeded in patronizing a new generation of women whose ambitions went far beyond becoming “a good little Maxwell Housewife,” as a 1965 ad put it, but also ignored the fact that a younger generation had become more susceptible to the lure of soft drinks, particularly cola, sold to the soundtrack of popular music.

“Food goes better with, Fun goes better with, you go better with Coke,” sang one song at the time, foreshadowing the way soft drinks would take over as the preferred dinner companion (Prendergast, 2010, pp. 255e258).

More: The Pioneering Phase: Uses, Meanings, And Structures Of Coffee