Coffee Origins Of Yemen: Yemen has been commercially producing coffee for longer than any other country, and its coffee is different, if not difficult, and certainly uncommon. This article will focus on introducing the coffee origins of Yemen.

Despite a long history of high demand for Yemeni coffee, the trade has never become commoditized. Yemen is unlike any other country, from its coffee types to terraced cultivation to processing and trading.

Coffee Origins Of Yemen

Coffee came to Yemen from Ethiopia, either through trade or those making pilgrimages from Ethiopia to Mecca, and was well established in the country in the 15th and 16th centuries. Export of its coffee introduced the world to the port of Mocha, and I think it is fair to say that ‘mocha’ is probably the most confusing word in all of coffee’s lexicon

Only 3% of Yemen’s land is suitable for agriculture, with water being the most significant constraint. Coffee is cultivated on the terraced ground at high altitudes, which needs additional watering to maintain the tree’s health. Many farmers rely on nonrenewable deep subterranean water supplies, and there is some worry about stock depletion.

Because soil fertilization is not very prevalent, there is an additional issue of soil nutrient depletion. All of these conditions, together with the remoteness of the coffee-producing regions, help to explain the vast number and variety of heirloom Arabica types found throughout the nation, the majority of which are unique to their respective growing regions.

Yemen’s coffee is picked by hand, with pickers visiting a tree several times in a season. Despite this, selective picking is not particularly commonplace, with underripe and overripe cherries often being harvested.

Whole cherries are usually dried in the sun after harvesting, often on the roofs of the farmers’ homes. Rarely do these roofs provide enough space, so the cherries are often piled too deep to dry correctly, resulting in defects such as uneven drying, fermentation, and mold.

Each producer may only grow a very small amount of coffee. Data from the 2000 census shows that around 99,000 households produced coffee, and based on estimates of production the average household produced just 113kg (249lb) of raw coffee that year.

Yemeni coffee continues to enjoy significant worldwide demand, with Saudi Arabia accounting for over half of all exports. This, along with restricted output and relatively high manufacturing costs, leads to high sales prices.

The traceability of coffee has not improved as a result of growing demand, and it can still pass via a network of middlemen from the farmer to the exporter. Coffees can also linger for a long period (sometimes years) at the export point since some exporters sell their oldest inventories first and store their fresh crops in underground tunnels.

Since the civil war began in 2015, coffee production in Yemen has been badly affected. The actual volumes produced have decreased only a little, but exports have fallen to a little over half of what they were before the war. Be aware that there has been an increase in the fraudulent mislabelling of Ethiopian coffees, with many being presented as Yemeni coffees to try to meet the existing demand and achieve a premium price.

The Term ‘Mocha’

Originally, the word referred to the port in Yemen from where coffee was exported. This spelling soon changed to ‘Moka’, and the term was used to describe the potent and pungent coffees produced in Yemen. Some naturally processed coffees from other countries are still described this way, such as Moka Harrar from Ethiopia.

Yemeni coffees were frequently combined with Java coffees, giving birth to the MochaJava blend. However, because the name was not trademarked, it became a type of stylistic phrase used by numerous roasters to describe the flavor of a particular blend they developed rather than the origins of the individual coffees. The present use of the term “mocha” to denote a combination of hot chocolate and espresso only adds to the consumer’s confusion.

Qesher

Qesher, also Q’shr or Qishr, is a by-product of coffee production. It is the dried, but not roasted, husks removed from the coffee cherries. In Yemen, these husks are often brewed like tea as a way to consume a form of coffee. More recently, producers in Central America have been experimenting with the same product, there called cascara. This is usually just the dried fruit of the cherry, rather than both the fruit and the dried parchment seen in Qesher.

Traceability

Trying to understand exactly where coffees come from in Yemen can be extremely confusing. Often the name of the coffee will include the term ‘Mocha’, indicating the port from which it was exported. Usually, coffees are only traceable back to a particular region within Yemen, rather than to the farm where they were produced. It is also common to see the local names for different coffee varieties used to describe the coffee, such as Mattari.

A higher level of traceability does not always imply a higher level of quality. Before export, various coffees are frequently mixed together and sold under the most valuable label. Yemeni coffee’s popularity stems from its unique, wild, and spicy flavors, which are due in part to manufacturing flaws.

If you want to taste Yemeni coffee, it’s best to get it from a provider you already know and trust. To locate a good sample, roasters will have to cup through a lot of bad ones. When you buy anything on the spur of the moment, the chances are stacked against you, and you may wind up with something that tastes filthy, rotten, and nasty.

Taste Profile

Wild, complex and pungent, a completely distinctive coffee experience, different from other coffees around the world. For some the wild, slightly fermented fruit quality is offputting, while others prize it highly

Growing Regions

Population: 25,408,000

Number of 60kg (132lb) bags in 2016: 125,000

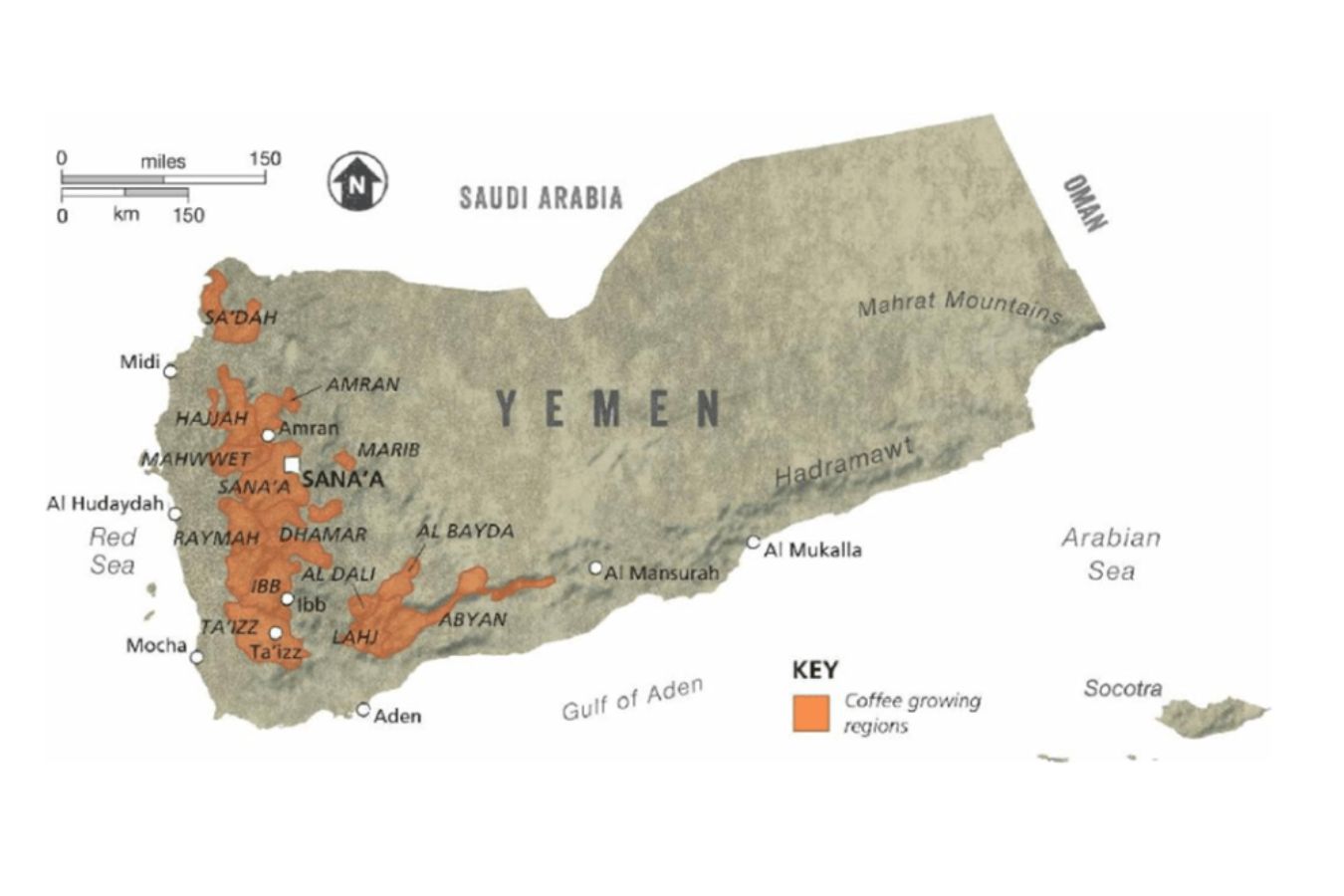

Please note that westernized spellings of place names in Yemen can vary quite dramatically. Each region described in Yemen is a governorate, rather than a geographically deĀned region. Yemen has 21 governorates, but only 12 grow coffee and even fewer are key producers.

Sana’a

Many of the premium coffees exported from Yemen bear the names of the varieties grown in this region. Confusingly, Mattari can be used to describe a region (around Bani Matar), and the name of the variety is probably derived this way.

The region is based around the city of Sana’a, one of the oldest continuously populated cities on earth, and at 2,200m (7,200ft) above sea level, also one of the highest. As a region, this is the largest producer of coffee in the country.

| Altitude:

Harvest: Varieties: |

1,500–2,200m (4,900–7,200ft)

October–December Heirloom varieties such as Mattari, Ismaili, Harazi, Dawairi, Dawarani, Sanani, Haimi |

Raymah

This small governorate was established in 2004. It produces a reasonable amount of the country’s coffee and has increasingly been the focus of water-management projects by nongovernment organizations to help increase coffee yields in the area.

| Harvest:

Altitude: Varieties: |

October–December

Average of 1,850m (6,050ft) Heirloom varieties such as Raymi, Dwairi, Bura’ae, Kubari, Tufahi, Udaini |

Mahweet

Located south of Sana’a, the city of At-Tawila rose to prominence between the 15th and 18th centuries as a hub for coffee-growing in the region. The city was a collection centre for coffee before it headed to ports for export.

| Altitude:

Harvest: Varieties: |

1,500–2,100m (4,900–6,900ft)

October–December Heirloom varieties such as Mahwaiti, Tufahi, Udaini, Kholani |

Sa’dah

This governorate has unfortunately been plagued by civil war since 2004. Confusingly sada is an Arabic term for black coffee and is popular throughout the Middle East, often served with the addition of spices.

| Altitude:

Harvest: Varieties: |

Average of 1,800m (5,900ft)

October–December Heirloom varieties such as Dawairi, Tufahi, Udaini, Kholani |

Hajjah

This is another small producing region, centered around the capital city of Hajjah.

| Altitude:

Harvest: Varieties: |

1,600–1,800m (5,200–5,900ft)

October–December Heirloom varieties such as Shani, SaĀ, Masrahi, Shami, Bazi, Mathani, Jua’ari |

More: Coffee Origins Vietnam