Coffee Origins: Indonesia – The first attempt to cultivate coffee on the Indonesian islands failed miserably. The Dutch Governor of Malabar in India delivered a few coffee seedlings to the Governor of Jakarta (then Batavia) in 1696.

After the first consignment of plants was lost in an old in Jakarta, a second batch was sent out in 1699. These plants grew to be quite successful. This article will focus on introducing the coffee origins of Indonesia.

Coffee Origins: Indonesia

Exports of coffee began in 1711 and were controlled by the Dutch East India Company, usually referred to by its Dutch initials VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie). Coffee arriving in Amsterdam sold for high prices, 1kg (2lb) costing nearly one percent of the average annual income.

The price slowly came down during the 18th century, but coffee was undeniably very profitable for the VOC. However, as Java was under colonial rule at the time, it was not at all profitable for the farmers who grew it.

In 1860 a Dutch colonial official wrote a novel entitled Max Havelaar: Or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company, which described the abuses of the colonial system.

This book had a lasting impact on Dutch society, changing public opinion about the way coffee was traded and the colonial system in general. The name Max Havelaar is now used for ethical certification within the coffee industry.

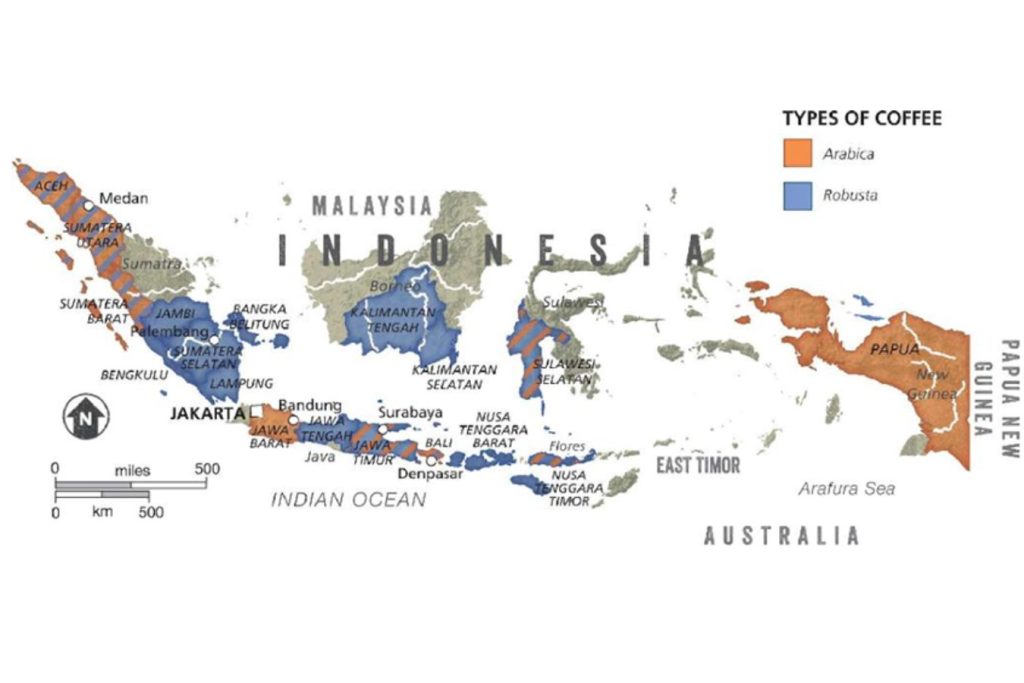

Initially, Indonesia produced only Arabica, but coffee leaf rust wiped out much of the crop in 1876. There was some attempt to plant the Liberica species instead, but that also suffered at the hands of leaf rust, so production switched to the disease-resistant Robusta. Today Robusta still makes up a significant portion of the crop.

Giling Basah

The ancient postharvest practice of imparting Basah is one of the most distinctive characteristics of coffee cultivation in Indonesia, and the basis of Indonesian coffee’s extremely contentious flavor. The washing and natural processes are combined in this hybrid technique. The cup quality improves dramatically as a result of the semi-washed procedure.

It drastically lowers the acidity of the coffee while also appearing to enhance its body, resulting in a softer, rounder, and heavier-bodied cup. It does, however, bring a variety of new flavors, some of which are vegetal or herbal, some of which are woody or musty, and some of which are earthy.

This isn’t to claim that all coffee produced in this manner is of consistent quality or has undergone taste standardization. The quality of these coffees varies significantly.

The flavor of semi-washed coffees is particularly divisive within the coffee industry. If a coffee from Africa or Central America displayed the same flavors, regardless of how well the process was done, it would be considered defective and rejected immediately by any potential buyers.

However, there are many people who find the intense and heavy-bodied cups of coffee brewed from Indonesian semi-washed lots delicious, and so the industry continues to buy them.

In recent years, specialty buyers have encouraged producers throughout Indonesia to experiment more with the washed process to allow some appreciation of the taste of the variety and the land rather than the dominant flavors of the process. We shall see if demand for these coffees is strong enough to encourage widespread production of cleaner coffees, or if the industry will see continued demand for semi-washed lots and simply continue to meet it.

Kopi Luwak

In Indonesia, Kopi Luwak refers to coffees that are produced by collecting the droppings of civet cats that have eaten coffee cherries. This semi-digested coffee is separated from fecal matter and then processed and dried.

In the last decade, it has come to be seen as an amusing novelty, with unattributed claims of its excellent āavours, and it sells for spectacularly high prices. This has caused two main problems.

Firstly, the forgery of this coffee is quite commonplace. Several times more is sold than produced, and often low-grade Robusta is being passed off at high prices. Secondly, it has encouraged unscrupulous operators on the islands to trap and cage civet cats, force-feed them with coffee cherries, and keep them in terrible conditions.

I find Kopi Luwak abhorrent on just about every level. If you are interested in delicious coffee then it is a terrible waste of money. One-quarter of the money you might spend on a bag could instead buy you a stunning coffee from one of the very best producers in the world.

I can only regard the practice as abusive and unethical and I believe people should avoid all animal-processed coffees, and not reward this despicable behavior with their money.

Traceability

While coffees from particular farms can be found on the islands, they are extremely uncommon. Those that have been traced and properly washed (rather than semi-washed) are, nonetheless, well worth trying.

Because most coffee is grown by tiny farmers with approximately 1–2 hectares (2.2–4.4 acres) of land, coffee is generally only traceable to a certain washing station or area. There is a lot of diversity in the quality of these regional coffees, so they’re a bit of a gamble.

Taste Profile

Semi-washed coffees tend to be very heavy-bodied, earthy, woody, and spicy with very little acidity

Growing Regions

Population: 263,510,000

Number of 60kg (132lb) bags in 2016: 11,491,000

From its origins in Java, coffee slowly spread around the other islands in the region, Ārst to Sulawesi in 1750. It didn’t reach Northern Sumatra until 1888, Ārst being grown around Toba lake, and eventually appeared in the Tawar lake region in Gayo in 1924.

Sumatra

The province of Aceh in the north, the Lake Toba region in the south, and, more recently, coffee production in the south of the island around Mangkuraja are the three primary growing regions in Sumatra. Coffees from Takengon or Bener Mariah in Aceh, and Lintong, Sidikalang, Dolok Sanggul, or Seribu Dolok surrounding Lake Toba, may be traced to smaller localities within these regions. It’s only recently that traceability has been brought down to this level.

It was formerly usual to find coffee marketed under the label ‘Sumatra Mandheling.’ The word Mandheling relates to an ethnic group on the island, not a location. Mandheling coffees were frequently assigned a rating of 1 or 2.

Although the rating appears to be focused on the cup quality rather than the green coffee, as is more common, I would be cautious to suggest all grade 1’s because the awarding may sometimes appear arbitrary.

It is unusual to separate different varieties into different lots, so most Sumatran coffee will probably be a mixture of unknown varieties. Coffee from Sumatra are shipped out of the port of Medan, but the hot, humid climate can have a negative effect on the coffee if it is left on the dockside too long before being shipped.

Altitude: Aceh 1,100-1,300m (3,600–4,300ft), Lake Toba 1,100-1,600m (3,600– 5,200ft), Mangkuraja 1,100-1,300m (3,600–4,300ft)

Harvest: September–December

Varieties: Typica (including Bergandal, Sidikalang, and Djembe), TimTim, Ateng, Onan Ganjang

Variety Names

Variety names in Sumatra can be a little tricky. Most of the Arabica seed stock initially brought to the island would have been derived from the strain of Typica that was taken from Yemen. In Sumatra, this is often called Djember Typica, but it should be noted that Djembe also refers to a completely different variety (a less superior one) found in Sulawesi.

It is common to see varieties that have, at some point, been cross-bred with Robusta. The best-known hybrid is called the Hybrido de Timor, a parent of the more common Catimor variety. In Sumatra, it is often called Tim Tim.

Java

It is more common to Ānd large coffee estates here than anywhere else in Indonesia, due to the colonial history and practices of the Dutch. The four largest farms, previously government estates, cover over 4,000 hectares (8,800 acres) between them.

For a long time, the island enjoyed a stellar reputation for its coffee, although I am sure it was not long before other coffees came to substitute the real thing in the ‘Mocha-Java’ blend of a great many roasters. Javan coffees commanded huge premiums for a long time, although prices fell towards the end of the 20th century.

Much of the coffee is planted on the east side of Java, around the Ijen volcano, but there are producers on the west side of the island, too.

| Altitude:

Harvest: Varieties: |

900-1,800m (3,000–5,900ft)

July-September Typical, Ateng, USDA |

Old Brown Java

Some estates in Java choose to age their coffee before export, for anything up to Āve years. The raw coffee beans turn from the blue-green commonly associated with semi-washed coffee to a muddy shade of brown.

Once roasted there is no acidity left in the coffee whatsoever, and there is an intense pungency and woodiness that some enjoy. However, if you like your coffee sweet, clean, and lively, you may well hate it.

Sulawesi

Most of the coffee from Sulawesi is produced by smallholders, although there are seven large estates that make up about five percent of the total production. Most of the Arabica on the island is grown high up around Tana Toraja. To the south is the city of Kalosi, which became a kind of brand name for coffee from the region.

There are two other less well-known coffee-growing regions: Mamasa to the west, and Gowa south of Kalos. Some of the most interesting coffees from the island are fully washed and can be exceptionally enjoyable. I would recommend seeking them out if you get the opportunity.

The semi-washed process is still common though, and the island also produces a good amount of Robusta. Coffee production can be somewhat disorganized throughout the region, as many smallholders grow coffee for supplemental income, concentrating their efforts on other crops.

| Altitude:

Harvest: |

Tana Toraja 1,100-1,800m (3,600–5,900ft), Mamasa 1300–1700m (4,300–5,600ft), Gowa average of 850m (2,800ft)

May-November S795, |

| Varieties: | Typicas, Ateng |

Flores

Flores is a small island about 320km (200 miles) to the east of Bali, and among the Indonesian islands, it was a latecomer to both growing coffee and developing a strong reputation for it. In the past, it was not uncommon for a large portion of the coffee from Flores to be sold internally or blended into other coffees rather than being exported as ‘Flores coffee’.

The island has a mixture of active and dormant volcanoes, which have had a positive effect on the soils. One of the key growing regions in Bajawa. In terms of coffee processing, the semi-washed process is still extremely common in the area, although there is some fully-washed coffee being produced.

| Altitude:

Harvest: Varieties: |

1,200-1,800m (3,900–5,900ft)

May-September Ateng, Typicas, Robusta |

Bali

Coffee came to Bali fairly late, and it was initially grown on the highland plateau of Kintamani. Coffee production in Bali suffered a signiĀcant setback in 1963 when the Gunung Agung volcano erupted, killing two thousand people and causing widespread devastation to the east of the island.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the government was doing more to promote coffee production, in part by handing out Arabica seedlings. One could argue that this had limited success, however, as today around eighty percent of the island’s production is Robusta.

While tourism provides the largest income for the island, agriculture is its biggest employer. In the past, Japan bought a substantial portion, if not all, of the coffee crop.

| Altitude:

Harvest: Varieties: |

1,250-1,700m (4,100–5,600ft)

May-October Typica and Typica derivatives, Robusta |